“Nobody’s perfect, but in the food world, beans are about as close as you can get.”

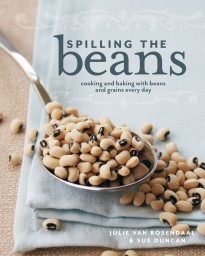

As perfect as beans may be, and as important as they may be in cuisines around the globe, they are conspicuously absent in standard North American cooking. I imagine this at least partly explains why omnivores are so easily baffled by the concept of a plant-based diet. As authors Julie Van Rosendaal and Sue Duncan point out in their cook book, Spilling the Beans: Cooking and Baking With Beans and Grains Every Day, one of the reasons for this is likely the fact that most people simply don’t know how to cook with legumes.

My aunt excitedly gave me a copy of this book and has been cooking up a storm with beans since she came across it– and she’s not a vegetarian or vegan. While some of the recipes include meat, many are vegetarian or offer instructions on how to make the recipe without meat. Perhaps writing a cook book about legumes without using a label like vegetarian is a good inclusive strategy. The likelihood that everyone will suddenly commit to vegetarianism is probably slim, but the chances that people will cook with less meat if they learn about the alternatives seem more likely. Perhaps a great gift idea for omnivores who like to cook?